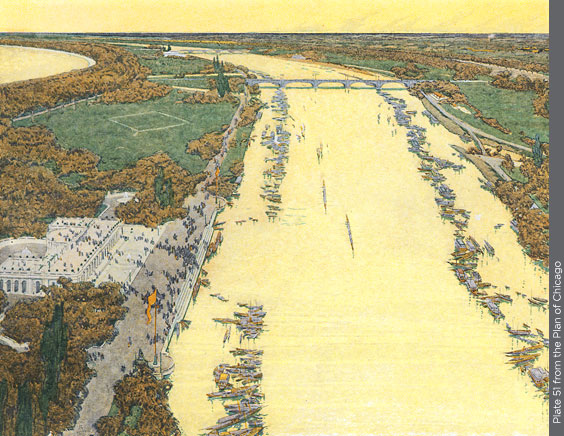

Offshore islands would shelter quiet lagoons, providing new shorelines and sites for pavilions and ballfields.

Northerly Island, first of a chain planned for the south lakefront, was created in the late 1920s (above). It was the site of the 1933-34 Century of Progress Exposition (below). After World War II, it was offered as the site for the United Nations, then became Meigs Field airport in 1948.